Episode 1 of the Building Bridges To Common Ground Series

4-minute read

Like a lot of people, I used to think that we humans are basically rational creatures who occasionally get emotional. We tend to picture ourselves as generally making logical decisions after carefully weighing evidence and considering our options—although emotions may sometimes interfere with our otherwise sound judgment.

But what if it’s actually the other way around?

An extensive body of neuroscience shows that the vast majority of our decisions are driven mostly by emotional and instinctual responses, which we later justify with logical-sounding explanations. Understanding this fundamental truth about how our brains actually work can transform how we see ourselves and how we interact with others.

Your Two Competing Systems

You have two distinct thinking systems that often compete for attention and control: the Lizard Brain and the Wizard Brain.

The Lizard Brain: Your Default Operating System

Your Lizard Brain (also called the reptilian or “instinctual brain”) evolved over millions of years with one primary mission: Keep You Alive. It’s constantly scanning your environment for potential threats or rewards, automatically categorizing everything it encounters as:

- Safe or dangerous

- Familiar or unfamiliar

- Rewarding or threatening

This system operates on emotion and instinct. It’s lightning-fast and energy-efficient. When it detects a potential threat—whether a physical danger or a challenging idea—it triggers immediate defensive reactions.

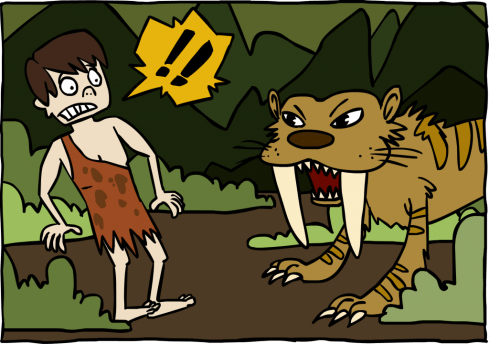

The problem? Your Lizard Brain can’t tell the difference between a savage predator and an opposing political point of view. Both can trigger the exact same defensive “fight, flight or freeze” reaction in our bodies.

The Wizard Brain: Your Executive Override

Your Wizard Brain, centered in your prefrontal cortex, is a relatively recent evolutionary development. It’s responsible for rational thought, complex analysis, and self-control. It’s what allows you to question your initial reactions, consider multiple perspectives, and make nuanced decisions.

The Wizard Brain is impressive but has significant limitations: it’s relatively slow, requires substantial energy, and often gets overridden when emotions run high. Think of it as a powerful but resource-intensive program that your brain only runs when necessary.

A Surprising Imbalance

Research in cognitive psychology reveals that a substantial majority of our mental processing occurs automatically, outside our conscious awareness. While we’d like to believe our thoughtful analysis drives most of our decisions, studies suggest otherwise.

Our Lizard Brain operates continuously and effortlessly, generating impressions, intuitions, and emotional responses that significantly influence our choices. Meanwhile, our Wizard Brain requires deliberate activation and consumes considerable mental energy.

This imbalance explains why we often make decisions based on emotion and instinct first, then use logical thinking afterward to find supporting evidence that will justify our decisions. And it makes sense, since the Lizard Brain is located right at the top of the brain stem, where all of our sensory input flows into the brain to be processed. The very next stop after that is the emotional center of the brain. It’s not that rational thought plays no role—it’s that it frequently serves to explain and validate what our intuitive brain has already decided.

Think of a person who tells you that they have decided to buy a new car. They’re excited about it, but it’s likely that they will also give you a few reasons for why it’s actually a smart decision. Their old car is getting up there in mileage and the brakes are worn, so it’s probably going to need some expensive repairs soon. That can help make it feel like the new car won’t actually be much more expensive, right? Of course, this is almost never true, but their Wizard Brain is doing its best to help justify what they have already decided they want. This is what we call rationalization–and it happens after the emotional center of our brain has already made a choice. Our brains tend to argue for what we want to be true.

This doesn’t mean we’re hopelessly irrational. Rather, it suggests that understanding the relationship between our intuitive and analytical thinking systems is crucial for better decision-making.

Intelligence vs. Emotional Awareness

You might wonder: Doesn’t intelligence make a difference? Won’t “smarter” people be more likely to use their Wizard Brains?

Surprisingly, conventional intelligence (as measured by IQ or academic achievement) doesn’t necessarily correlate with better decision-making when our emotions are triggered. Studies have shown that highly intelligent people are just as susceptible to emotional reasoning as anyone else—and sometimes even more so, because they can be better at constructing elaborate justifications for their beliefs and developing attacks on other people’s positions.

What seems to matter more is emotional awareness—recognizing when your Lizard Brain has taken control and consciously engaging your Wizard Brain. This skill is closer to what we might call wisdom than intelligence, and it can be developed regardless of your IQ score.

Why This Matters for Bridging Divides

When someone disagrees with us, their position likely isn’t the result of faulty logic— it may be rooted in different emotional responses that their Wizard Brain has rationalized. And of course, we may be doing the same thing to them.

One more important point: Facts alone rarely change minds. This is because facts require your Wizard Brain to process them, but most of the time the Lizard Brain is actually in charge. This isn’t because people are stupid or irrational—it’s because they’re human.

We need both the Lizard and the Wizard to function at our best. But it’s probably better when the Wizard rides the Lizard, rather than the other way around.

The next time you find yourself in an argument, ask yourself: “Which part of my brain is running my show right now? And what might be driving this other person’s responses?”

What do you think? Can recognizing our emotional foundations change how you’ll approach a disagreement? Have you noticed highly intelligent people (maybe even you) who sometimes get trapped in lizard-brain reactions? I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments below.