Episode 5 of the Building Bridges Series

4-minute read

Have you ever been part of a conversation about a difficult topic—politics, religion, parenting approaches, etc.—and watched it quickly spiral into frustration or outright conflict? My guess is that your answer is a resounding yes.

What if I suggested that many of these conversations go sideways not because of what was said, but because of the expectations we had going into them?

The reality is, having a successful conversation where there’s likely to be disagreement (without it becoming stressful or heated) may require you to let go of certain common expectations before you even get started. I got this idea from my experiences with the Braver Angels organization, whose purpose is no less than to restore the American spirit of working together.

Here are six expectations worth dropping before your next challenging conversation:

1. “I can change their mind.”

This might be the most damaging expectation of all. The truth is, we can’t force anyone to change their core beliefs. The only person you can reliably change is yourself.

When you enter a conversation determined to change someone’s mind, you’re setting yourself up for frustration. Instead, aim to understand their perspective better and perhaps plant seeds that might grow later.

2. “We can agree on the facts and have a logical discussion.”

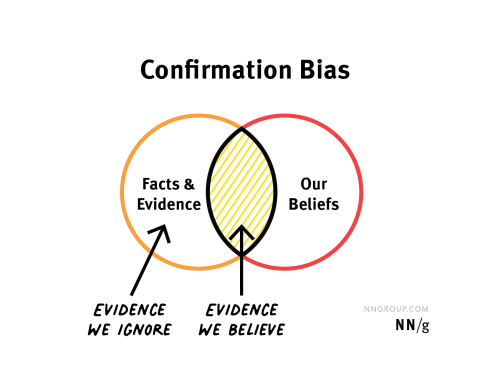

It seems reasonable to expect that we can agree on basic facts and follow logical progressions. But human brains don’t always work that way.

We all process information through existing belief filters. What seems like an indisputable fact to you might represent a threat to someone else’s entire worldview. Their resistance isn’t necessarily about logic—it’s about preserving their own psychological coherence.

3. “I am right.”

This certainty feels good, but it creates a major barrier to genuine dialogue. The moment we become absolutely certain we’re right about something is often the moment we stop being able to learn anything new.

Try entering conversations with the humility to admit you might be missing something. As they say on the podcast “No Stupid Questions,” you have to commit to the possibility that you might be wrong. This other person may know or have experienced something that you hadn’t ever thought of before.

4. “There will be a winner and a loser.”

Many of us unconsciously approach difficult conversations like debate competitions, where one person will emerge victorious and the other defeated.

Real life isn’t a debate tournament. The most productive conversations often end not with victory but with better understanding. Sometimes we need to let go of the need to win for a while.

5. “We should end up agreeing with each other.”

Agreement is a high bar that often isn’t realistic. A better approach is to focus on understanding why someone sees things differently than you do.

You still might not agree at the end, but at least you’ll know why and so will they. This understanding builds bridges even when consensus isn’t possible.

6. “If I keep an open mind to new ideas, they will too.”

Being open-minded is like being in shape—not everyone exercises regularly. Some people may not be ready to question their assumptions or consider new perspectives, especially in a first conversation.

It’s best to meet people where they are, not where you wish they were. Their openness may grow over time, especially if they see you modeling the curiosity and respect you hope to receive from them.

A Different Approach

Instead of these expectations, try approaching difficult conversations with:

- Curiosity about how someone else sees the world

- A willingness to listen, not just talk

- An assumption that this person may know something that you don’t

- Respect for the other person’s humanity, even if you don’t agree with them

- Patience with the process of building understanding

The goal isn’t to eliminate disagreement—that may sound nice, but we won’t ever get there. Instead, the goal can be to disagree better. By abandoning these six expectations, you create space for more productive exchanges, even if you’re talking about challenging topics. And if you can find at least some areas of common ground, that can be first step in finding ways to work together.