Episode 6 of the Building Bridges Series

3-minute read

Two people witness the same car accident. One sees reckless driving and demands stricter law enforcement. The other sees a tragic mistake and calls for better driver education. Same event, completely different conclusions.

Welcome to the power of worldview filters—the invisible lenses through which we see and interpret everything around us.

What Are Worldview Filters?

Think of your personal worldview as a pair of glasses you’ve been wearing so long that you’ve forgotten you have them on. These mental filters act as screens that determine:

- Which information gets your attention

- How you interpret what you see and hear

- What you consider important or trivial

- What seems obviously true or clearly false

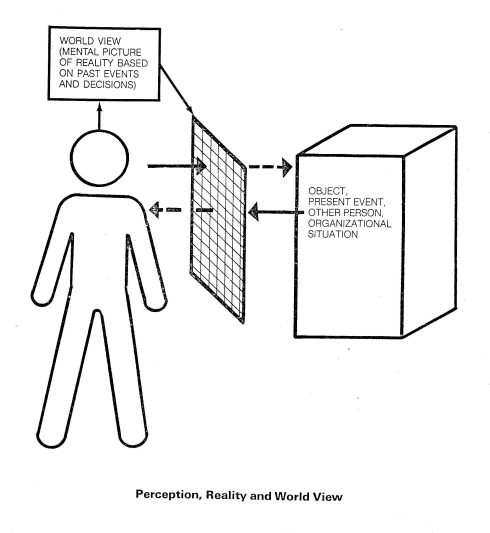

Your worldview isn’t just your opinion about specific topics—it’s the fundamental framework that shapes how you process all information and make sense of reality itself. As the diagram above shows, the same objective reality can pass through different people’s worldview filters and emerge as completely different perceptions—which explains why two people can witness the same event and come away with entirely different interpretations.

Where Do These Filters Come From?

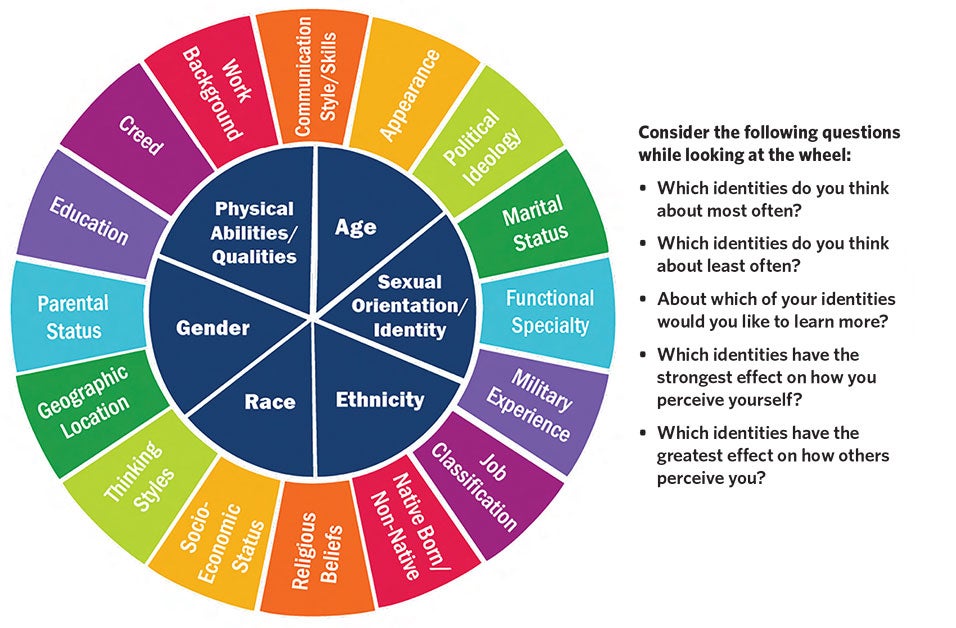

Our worldviews don’t form randomly. They’re built from the unique combination of experiences that make up our lives:

Life Events: Significant experiences shape our understanding of how the world works. A person who grew up during the Great Depression might have very different views about financial security than someone who came of age during the dot-com boom, when 22-year-olds were becoming millionaires overnight.

Cultural Environment: The stories, traditions, and values we absorb from our families and communities create deep patterns in our thinking, often operating below our conscious awareness. Religious and spiritual traditions are particularly influential, shaping our fundamental beliefs about human nature, morality, and life’s purpose in ways that affect how we interpret virtually every situation we encounter.

Social Circles and Information Sources: The people we spend time with and the media we consume reinforce certain ways of seeing the world while making others seem foreign or wrong. In our current information environment, algorithms for social media or search results often create echo chambers that reinforce our existing filters, rather than challenging them.

These filters work hand-in-hand with our brain’s natural tendency toward confirmation bias. Our Lizard Brain, focused on quick survival responses, uses these filters to rapidly categorize new information as friend or foe, safe or dangerous—noticing information that supports our existing beliefs while dismissing contradictory evidence.

Why Understanding Worldview Filters Matters

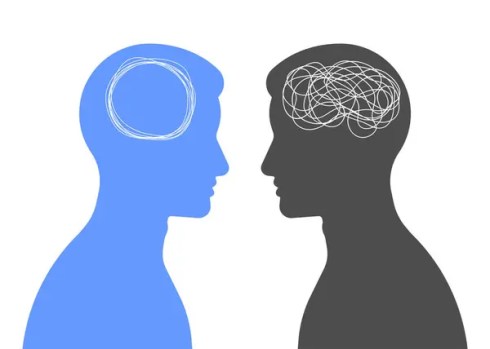

Since none of us have had exactly the same combination of life experiences, we’re naturally going to end up seeing some things very differently. Recognizing worldview filters is crucial because everyone has them, but most people don’t realize it. We tend to think our way of seeing things is simply “how things are” rather than one possible perspective among many. These filters operate unconsciously and often lead to misunderstandings when people wearing different worldview glasses discuss the same topic—it’s almost like you’ve learned to speak different languages.

Seeing Your Own Lens

The goal isn’t to eliminate your worldview filters—that’s impossible. Instead, the aim is to become aware of them to help understand how they might be controlling your thinking.

Try asking yourself:

- What major life experiences have shaped how I see the world?

- When I have a strong emotional reaction to new information, what might that tell me about my filters?

- How might someone with a completely different background interpret this same situation?

When you encounter someone who clearly sees the world differently than you do, try approaching them with genuine curiosity rather than judgment. Ask questions to help understand their perspective—not to prove them wrong, but to learn how their experiences shaped their worldview. This curiosity can lead to a much deeper understanding than arguing ever could. And that can make space for exchanging ideas.

The most profound conversations often happen when people recognize that they’re looking at the same reality through different lenses, rather than assuming one person is simply right and the other wrong. Next time you find yourself thinking “how can they not see the truth?”, remember: they might be wearing different worldview glasses than you are.

Which personal experiences do you think have most shaped your own worldview? Have you ever had a moment when you realized you were seeing something through a particular filter or bias? Are there some worldviews that are “right” and others that are “wrong”? Feel free to add your thoughts below.

Up Next: “Moral Foundations: Our Beliefs About How Things Are Supposed To Work”