Episode 3 of the Building Bridges Series

3-minute read

Have you ever wondered why two people can look at exactly the same information and come to completely different conclusions? Or why some people seem immune to facts that contradict what they already believe?

There’s a good chance that this is a result of a fundamental feature of the way our brains operate: Confirmation Bias. When it comes absorbing new information, you can think of this as a sometimes helpful but often troublesome gatekeeper.

What Is Confirmation Bias?

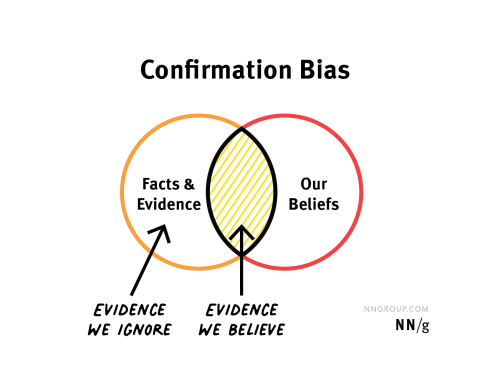

Confirmation bias is our natural tendency to notice, seek out, and remember information that supports what we already believe, while ignoring or dismissing information that contradicts those beliefs.

It’s like wearing glasses that filter reality, allowing you to see only what matches your existing worldview. The problem? We don’t realize we’re wearing these glasses. We believe we’re seeing the full, objective picture.

Your Brain’s Filter System

Your brain processes millions of bits of information every second, but you’re only consciously aware of a tiny fraction of it. To avoid getting overwhelmed, your brain uses shortcuts to decide what deserves your attention.

One of these shortcuts is to prioritize information that confirms your existing beliefs, since that’s much faster and requires a lot less energy. This happens in three key ways:

- Selective attention: You naturally notice things that support your beliefs and overlook things that don’t.

- Biased interpretation: When faced with ambiguous information, you interpret it in ways that support your existing views.

- Selective memory: You remember evidence that confirms your beliefs better than evidence that challenges them.

This isn’t something only “other people” do. We ALL do it, regardless of education level, intelligence, or political leaning.

The “That’s Interesting” vs. “That’s Wrong” Test

Here’s a simple way to spot confirmation bias in action: Pay attention to your immediate reaction when you encounter new information.

If the information seems to support your existing beliefs, you likely think, “That’s interesting!” or “I knew it!” You accept it easily, without much scrutiny.

If the information contradicts your beliefs, your first thought is probably closer to, “That’s wrong!” or “That can’t be right.” You immediately look for flaws or reasons to dismiss it, which often includes questioning the credibility of the information source.

The stronger your reaction, the more your confirmation machine is probably at work.

Why It’s So Hard to Overcome

Our confirmation machine isn’t just a minor glitch—it’s a powerful force that shapes how we see the world. And there are several reasons it’s so difficult to overcome:

- It operates largely unconsciously. We don’t realize we’re filtering information.

- It feels good to have our beliefs confirmed. Being right gives us a small dopamine reward.

- Challenging our beliefs can feel threatening, triggering our brain’s defense mechanisms.

- We’re surrounded by people who often share and reinforce our biases.

- If you engage in social media, powerful algorithms are restricting what you’ll see to content that you’ve already shown an interest in.

Remember when I mentioned in my post about our two brains that the Lizard Brain plays a leading role in our decision-making? Well, confirmation bias is one of its favorite tools.

Why This Matters

Confirmation bias isn’t just an interesting psychological quirk—it’s a key reason we’re so divided on important issues. When we only see evidence that supports our existing beliefs, we drift further apart instead of finding common ground.

Understanding confirmation bias doesn’t mean you’ll suddenly be free from it. But awareness is the first step. The next time you feel strongly about something, try asking yourself: “Am I seeing the full picture here, or is my confirmation machine filtering my view of reality?”

What do you think? Have you caught your confirmation machine in action recently? Which beliefs or stories might your brain be working to protect? You’re invited to add your thoughts below.